I am overwhelmed at the response – from friends and strangers alike – to this feature, published this weekend in Fairfax Media’s Good Weekend magazine. The reaction has been deep, gentle and sad for me – I hadn’t expected my words to touch people as they have, or to be so familiar to so many, or to stir quite so many tears. Good, I hope, will come of them…

Buying time, Good Weekend magazine, 25 September 2016

With early-onset Alzheimer’s comes the accentuating of deeply-ingrained habits, writes Daisy Dumas of her mother’s struggle.

My mother slowly, clearly, says her name. As we drive along the motorway towards London Heathrow airport, I next ask her age. “1948.” And today’s date? “2016. 2015. Monday.”

I’ve flown from Australia to England to surprise my parents for a family celebration and, with the jet lag still raging, it is time to turn around and head back to my home in Sydney. As my 70-year-old father drives, I gently interview my 67-year-old mother as a way to collect as much as I can, at this stage, of her. Of her words, her memories, herself. I’ve done this several times over the past year or two and, on this unseasonably cold April evening, the progressing damage to her brain is blunt and frightening.

“The last one with me was. The last one is. It is 1970 with me,” she says, when I ask what she is doing now.

It is not just through her delayed, oblique answers and morbidly crippled language that my mother’s dementia is evident. She no longer drives, plays piano, cooks well, reads, concentrates for more than a minute or stays active. She stamps her foot and slaps my father, to whom she has been married for 44 years. Her vocabulary, once as sparkling as she always looked, is limited to about 50 words.

And these days, she buys. Like a toddler who cannot be dissuaded, my mother sees something she wants and will not be stopped from owning it. She spends money without sensing its value or the pointlessness of what she is buying.

This morning, a delivery arrived at her front door: a $200 pair of shoes. She has a similar pair on her feet. There are two unopened bottles of the same Chanel perfume on her dressing table. (Beauty routines, I suspect, will be one of the final traits to be prised away from her by this creeping, stultifying disease.) In the fridge are five identical tubs of butter. The kitchen cupboards hold similar stockpiles, bought, then forgotten.

Every day, mail-order catalogues arrive at my parents’ home in southern England, a steady stream of pictures of women smiling “buy me” in their wrap dresses and Santorini swimsuits. That my mother can’t tell me the date but can quietly dial the orderline number – in unmissable, bold print – ask for the skirt on page 23, give her credit-card details and, days later, receive yet another item she will never wear, bewilders my father, three sisters and me.

We swing between stress and horror as she eats into the savings she should be protecting to pay for the care home we are told to expect. We feel sick when we see the parcels arrive, another useless dress, another sun hat that will never see the light of day, another Frozen DVD for a granddaughter who has three from her granny already. And the internet and technology make it easier.

One of my older sisters once attempted to stop an opportunistic sales woman in a major department store from upselling a well-known brand of cosmetics to my mother. A scene loudly escalated, my sister backed down to keep the peace and my mother left with more than $400 of products after approaching the counter to replace just one. She often hands over notes, finding coins too much of a muddle, and never checks her change. The pleasure she might have once derived from those newly procured shoes or creams has, like so much of her character, gone AWOL. Yet, for her, it provides a vestige of control over an ever-slipping reality.

As with about 7 per cent of those with dementia, my mother’s is early onset, affecting those younger than 65. For her, the degenerative disease is laying bare some of her deepest, most ingrained habits. Shopping is one – she’s always loved fashion, buying presents and, as a once-excellent cook, keeping a full, organised kitchen. “Correspondence”, a role she has always taken very seriously, is another. She will sit writing emails and postcards for hours a day, sending fragmented inside-out sentences to her family and friends around the world. Their contents form the most solid, sad record we have of her slide from poet and artist to a woman we struggle to understand, who confuses strangers, snaps at her husband and torments herself more than anyone else.

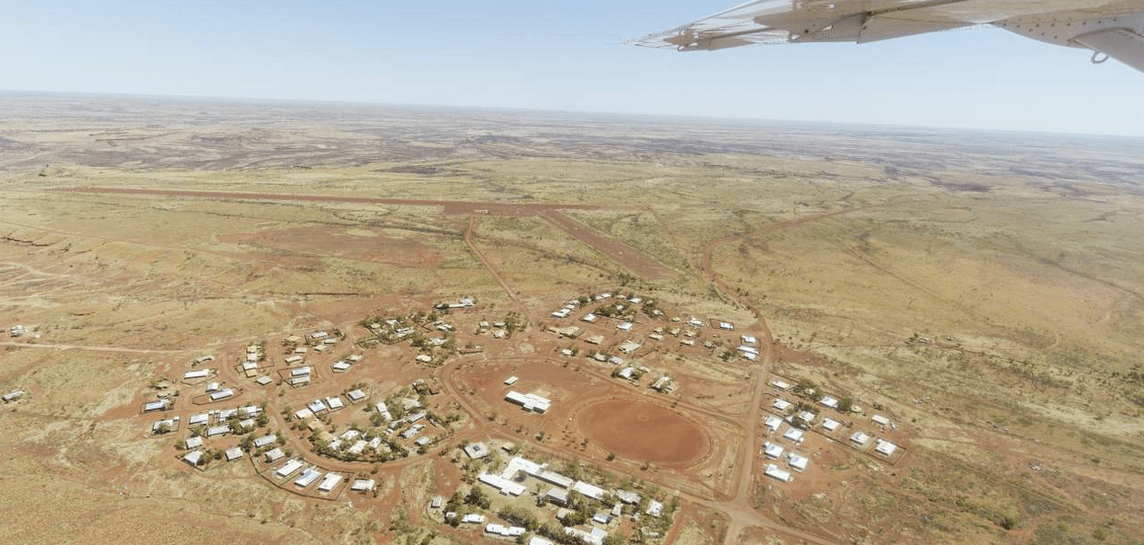

Born in Maryborough, Queensland, the daughter of a bank manager, my mother grew up filled with wanderlust as her family moved around the outback. She would reminisce to us about parcels wrapped and tied with string by the post-office lady with long, red fingernails and matching lipstick, symbols of life beyond Charters Towers. Dressed in miniskirts, thigh-high boots and with a brown bob, she ended up in the Swiss Alps, met my father, an army man from the west of England (cravat, loud laugh, very unreliable fast car) and went on to have four girls while travelling the world as a diplomat’s spouse. Ever dutiful, she worked hard by his side, labouring over hors d’oeuvres for endless receptions and raising us with no help from nearby family.

Her mother, aunt and grandmother died of early onset Alzheimer’s and, as my mother turned 60, we all suspected something was up long before we admitted it. There were sudden moments of severe disorientation, for example. We now realise our need to repeat sentences was about something far less manageable than fading hearing. And before the strange lapses, there was a general fug as depression set in and her text messages and phone calls dropped off.

In June 2013, doctors confirmed what we dreaded.

As much as we reeled – and I won’t forget the vertigo-inducing moment a text message came from my sister containing the news – it came as no surprise to us; nor, I suspect, her. She had always half-joked about being next in line and whenever she spoke about her own mother, it seemed to come with the caveat of how she, too, would end up in her “beanbag” – her term for incapacity.

But none of us, most especially my mother, was prepared for the disease’s effects and the denial and traumatising dancing around the diagnosis that followed. Even the word “Alzheimer’s” became utterly taboo.

“There’s nothing wrong with me inside,” she used to say, and would lash out at those who dared mention what my father still calls “The Big A”. Frightened and angry at those who attempted to tell her she was sick, she blamed her “words” on a bout of typhoid a decade earlier. Everybody else had the problem, not her.

The changes are now so evident and fast-moving that we notice her vocabulary and parts of her character slip away even after a few days together. But besides her slumped cognition, she still seems young and relatively strong. She puts up a good fight, generally getting her message across despite her language now limited to the same curtailed words and phrases.

“You’re going upwards with upwards and upwards?” my mother will ask. Or, when I say goodnight, “I’ll see you again, today.”

Back on our drive towards the airport, as we pass Swindon and the motorway’s three choked exits to Reading, I ask where we are going. She is unable to answer and instead methodically lists everywhere she lived up until the age of 21.

We – all four daughters and our father – have tried everything to curb her perpetual shopping. By telling her she doesn’t need more shoes. By asking shop assistants to lie about not having a size in stock. We scour her email, remove her from mailing lists and return brochures. We cancel one credit card and put a daily limit on another (handy, but her spending is not on big items but lots of little things that add up) and we gently try, again and again, to reason with someone who doesn’t have any. As my father says, she has a newfound “sod it” attitude to life, childish in her abandonment of the social checks and filters she used to possess.

According to Alzheimer’s Australia, there are an estimated 353,800 people living with dementia in Australia, a figure that will swell to 550,200 by 2030 and almost 900,000 by 2050. Globally – because this is a problem that crosses borders – the problem is vast. The World Alzheimer Report 2015 makes for eye-opening reading: more than 46 million people live with dementia worldwide, more than the population of Argentina, it says, a total that is set to soar to an estimated 131.5 million by 2050. The current estimated worldwide cost of the disease is already $1.1 trillion, up to $1.34 trillion by 2018.

In Australia, one in 10 people aged over 65 – and three in 10 over 85 – have dementia. But the biggest wake-up call may be that one in four Australians is now aged over 55.

Like many carers of those people with dementia and Alzheimer’s, we are caught in an ethical dilemma that is only set to become much, much more common. “We know people with dementia find decision-making difficult; they purchase things they don’t need or can’t afford; they run up a debt easily,” says John Watkins, chief executive officer of Alzheimer’s Australia. “How do you protect someone from themselves when they do not wish to be protected?” asks Watkins. “How do you intervene when it is increasingly recognised that people’s individual capacity should be protected?”

Rather than relieving my mother of her freedom to make decisions for herself, the recommended strategy is now supported decision-making. (The old-fashioned but essential fallback, enduring power of attorney – a classic example of substituted decision-making that my sisters and I have in place for our parents – is probably not something to invoke over $5 tubs of butter or even $200 pairs of shoes.)

Empowering my mother in normal society for as long as possible is non-negotiable, given its known benefits for her wellbeing. It is her right to buy new shoes – and as many pairs of them as she likes – just as it is my right to make rash purchases and your right to sign up to yet another air miles’ rewards scheme.

But what can we do to protect our mother from being taken advantage of in a world that is all about the sell? A more robust and dynamic ethical code of conduct for retailers, perhaps, or an extended returns period for the mentally impaired? Or, one day, maybe, a coding system built into the electronic data in our bank cards and smart phones?

Retail is, I’m told, making efforts to face an inevitably growing problem. The Australian Retail Association (ARA) has devised a DVD with Alzheimer’s South Australia to guide retailers on customers with dementia. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anybody [suffering Alzheimer’s] upsold for the sheer hell of it,” says the ARA’s Russell Zimmerman. “I would hope to goodness I would never see a retailer do it knowingly.”

Yet surely all upselling is, for want of a better way of putting it, for the “hell of it”? And all sales techniques – online and otherwise – are designed to do one thing: to help a customer part with their cash.

What my mother exemplifies is blurry and hard to patrol. There is nothing illegal at play here. This isn’t about the frankly appalling risk of large-scale fraud, as in the case of Sydney dementia sufferers Edna Pearson and Herbert Luscombe, who both signed over millions to strangers before they died. This is about the moment when we have to curtail my mother’s right to make her own decisions. To remove her freedom to live as she wishes.

Before our ride to the airport on that otherwise dreary Monday, my older sisters walked around our parents’ town, visiting my mother’s routine stops. These are a lifeline to her, because, while the everyday, rude practicalities of living with this disease come secondary to its grinding, unfathomable sadness, they are what make it almost bearable or utterly grim.

The staff in the pharmacy know my mother well and have had dementia training. My sisters apologise as they return one of the bottles of perfume. The women behind the counter are unfazed and delightful.

The local chain cafe, too, is used to her; its staff tell my sisters she is always a pleasure to serve. Some children get to know their mums at the soccer pitch, others on the beach; for us, it was in a revolving handful of favourite cafes – my mother was their best customer. She orders her coffee by saying its price, and even behind the merciless mask of dementia, she still adores her regular cappuccino, just as she’s done for as long as I can remember. The old Mumma is still there in other ways, too. She hasn’t lost her cheekiness; we laugh together, hug often and sit watching TV – despite her impatience with each and every channel – our legs intertwined on the sofa.

A favourite photo of mine was taken around 1990, when my parents lived in Germany. It is my mother’s leaving party, as she prepares to move into yet another army quarter in yet another country. Her high cheekbones shimmer with blush as she smiles, holding a massive bouquet of native Australian flowers, flown in for the occasion. She wore her asymmetric patterned culottes that evening, and a shoulder-padded bolero jacket. God, she was cool.

We don’t leave my mother alone these days. At Heathrow’s Terminal 2, before our well-rehearsed goodbyes, I walk her to the ladies’, before a final cup of tea together. Throughout, she says on repeat, “I’ll see you again.”

She’s right, I will see her again, soon. But I won’t see her like this. Next time, another watered-down version of my mother will greet me. And when we farewell, yet another will hug me goodbye.

National Dementia Helpline 1800 100 500. Donate to Alzheimer’s Australia.