The TV is bringing news from Homs.

It is not good. It never seems to be, these days. She shakes her head, wrings out the dishcloth and folds it over the cold metal of the sink’s edge. Her nail polish, she notes, stirring the young jam – as the news anchor reels off a dark roll-call of deaths, bombs, Assad dissidents and maimed women and children – is chipped, a blander colour will be better, next time.

She can hear children playing in the distance, the hum of a car engine, the white noise of well-to-do suburban life. The afternoon sun catches her engagement ring, notched, filed down with the scratches and bumps of her years.

Her Syria had been a different place. Dark and angry, perhaps, but only to her and those who dared to question. Spring was a season, not an uprising, Hama, just north of Homs, was a town quietly mending itself, removing the splints from its own fractured past – a place where concrete trees sat alongside silent merry-go-rounds, waiting for life to trickle back into the play-parks and night markets and for real, green shoots to take root, to ramble over the pain of 1982.

It was just two years ago, almost to the day. Madoff had stolen her money. She liked the irony of his moniker – Bernie made off with her life savings – it gave the horrible, terminally disappointing affair a sneeringly sardonic edge, reluctant as she had been to acknowledge the clogging weight of her sadness.

She had gone to the Middle East to forget. To cloud her memories with cloying Omani frankincense, to scrub and scrape the layers of folly – a four-year-old knows how to diversify, for god’s sake – away with rough Turkish bath cloths, to close her eyes and be swallowed by the dark depths of unquestioning Dead Sea mud.

She’d tried listening to Eckhart Tolle, willing the man’s gentle humility to infiltrate her jaggering, all-pervading – and far from dignified – reactions. She wanted to let go of the hate, the tortured regret, the anger, but try as she might, the Germanic, ordered lull failed to permeate. She tried exercise; Janine had signed her up to the brazen Zumba classes at 24-hour Fitness. As much as she wanted to give in to the deafening music and bizarre air pumping, it wasn’t for her. She even sat down in front of a handkerchief of green felt, attempting to surrender her concentration to bridge classes. But North meant looking across to South, and South, to her, meant Wall Street. West was the World Trade Center site and East – eastwards led her to Syria.

Tolle would be pleased here, she thought, as a muezzin bumped his holy microphone, flooding the morning air with a brief haze of static. The devout of Aleppo dutifully made their way to their local mosques, every prayer call a reminder of the now; every day neatly split into chunks of present. With each unrolling of a prayer mat came another window – just a few hours – of redemption. No room to fixate on much else. But they’re all looking forwards, or backwards, too, she thinks. We can’t help it.

There may be no future, but there is hunger, she says to herself.

‘Excuse me, madam?’

‘I’ve just realised how hungry I am,’ she tells her guide with a wide smile, embarrassed at her self-indulgence. Here he is, trussed up in his Western shirt, neatly ironed, his side-parting glossed and rigid. He was recommended by Janine’s sister who has a friend who worked at the embassy in Damascus, but still she found it hard to trust the man, his dark eyes too deep-set, his manner too earnest to be taken seriously.

Beyond the kitchen window, a car alarm rings somewhere in the distance, towards the parking lots around the mall.

She catches herself smiling, now, as she goes to the glass cupboard, pulls its glossy door open, jingling its sparkling insides. High balls stand to attention next to Champagne flutes, showy red wine glasses take up too much space. She wipes each rim as she sets the crystal down, its footprint waiting in the dark. She moves to the cupboard below, grips the solid, weighty glass of an empty jar and brings it into the spring light.

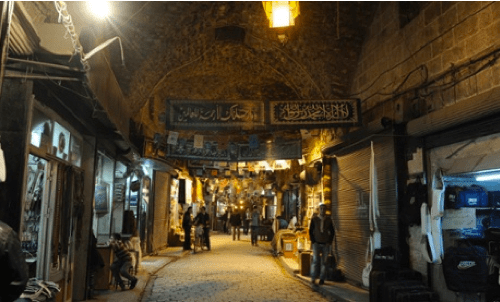

Hama, she remembers, was chilling. Homs was awake to change, but it was Aleppo that beguiled her, that stole her self-pity. Ba’athists had not boiled its character down to life or death.

She listened, in the gnarled souk, to her guide tripping over his new-found English, finally forgetting herself, her lost thousands, as she sank further into its epic, crepuscular story.

‘Theses streets have been constant-ily lived in for around 7,000 years. Since fifth millennium bee-cee.’ He jolts at the end of each sentence, like an out-of-breath sprinter with a microphone pressed into his panting face. Before Jesus, before New York, before Madoff. Before the East and the West and continents and maps. Before families and marriage and law. Before it all.

She excused herself, apologising, and wrapped her new shawl closer to her head, breathing in its dusty, haggled-for camouflage. She has a hunger she hasn’t felt since youth.

‘I could eat a horse,’ she says, emboldened, out loud.

It’s dark under the metal roof of the meandering lanes, cramped, loud, uneven under foot. She is a white pillar in a sea of black shrouds. She looks around for somewhere to eat.

Tea is being poured, streaming from a stainless steel pot a foot above the tiny glass. Small stools, their puffy pillows coated in clear plastic, are huddled around upturned crates, silver discs perched atop their wooden lattices. Strip lighting hangs above pyramids of oranges, apples, watermelons and bunches of spiky mint.

‘There’s an Arabic saying’, her guide had earlier told her as she walked past a domed heap of dried fruit, ‘that goes, buchra fil mish mish.

‘It means: tomorrow there will be apricots.’

‘Apricots?’

‘It means it might not come – insh’Allah. I think in English you have something similar: bigs will fly’.

Pigs might fly. If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. She is resigned to that, now.

She can’t speak much Arabic. A bearded man, plump belly pushing against stretched cotton, focuses on her, unsmiling, distracted, seeing through her. She smiles, points to the stacks of bread being delivered from a cart in the teeming alley.

‘Chai, min fadlak.’ It’s all she knows. So far from her usual world of two-car garages, coupons, driving ranges and tumble-dryer cloths.

There are no spare stools. She perches on a step in a doorway, thousands of miles from home, broke. Earthquakes, Saladin, the gateway to Palmyra. Medieval fortresses and recipes unchanged for centuries. War and extremism. Broken families, new jobs, car accidents, infidelity, robbery, lottery wins: Context is everything. Time throws a finer focus onto what counts.

Ten eyes are squarely focused on her body. On her femaleness, on her breasts under her fine cotton shirt, on her mascaraed eyelashes, on her sandaled feet. Her milky white wrists and the wizened ring.

Like the skin on setting jam, she is cocooned by the shield of her scarf, by her foreignness, by the Ponzi scheme. Nothing, she realises, will touch her.

She is served. Shokran. she is impermeable, she has decided, to their stares, their lazy daydreams.

And there it is. A green plastic plate, a smeared glass filled with sweet mint tea. A white curl – so bright and luminous it seems utterly at odds, lost in the fetid grind of the great souk – of fresh, stretched curd cheese. A dollop of brutishly alive apricot jam sits on its edge, like a bruised, sun-warmed harvest straight off a heavy tree, and teetering above is a swollen khobes bread, ready to burst with relief and spill its burning steam.

She eats the bread, cheese and jam. She eats the fruit, grain and animal. She has one glass, two, three of tea. Her mouth wraps around hot, cold, salt and sugar. She bites on a history, eats a civilisation and chews, systematically putting away her old life, swallowing her indignation.

‘I’ll tell you about your father’s travels one day,’ she remembers her Bath-born mother once saying, as she carefully measured pounds of sugar and bleeding fruit for jam-making. ‘He was a dreamer, a special man, but he never was clever with money. Wasted more than just himself. He wanted the world for you.’ Did he walk through Aleppo’s labyrinthine layers, did he step into a David Roberts painting, did he move and spend to forget? She still asks.

It’s getting dark now and cars have pulled into driveways. Shrieks and basketball hoops have given way to evening meals around polished wooden tables. It’s not the home she thought she’d end up in, the crystal is not hers, the prim pathway does not lead to a place that she owns.

Her batch of jam has thrown steam to the sides of the cool, clean jars and is now covered with leaves of wax paper. It sits, waiting, beneath tightly closed lids. She doubts that her son will chose to eat it alongside salty, fresh curds, she wonders whether his children will remember it’s their great-grandmother’s recipe. She prays, teat-towel in hand, that Aleppo may never change.

The front door slams and the TV is switched on. The bad news from Syria hasn’t ended.

(Written in April 2012 – before Aleppo was almost entirely besieged and its souk burnt out, belittled and all but ruined.)